The impact of microbes on human health is one of the most exciting medical advances in recent years

Over the last two decades, the amount of research on how little bugs that live on and inside us impact our health has increased rapidly. And the pace of microbiome research is only picking up.

Your body contains trillions of microorganisms (collectively known as the microbiota).

While some of them are linked to disease, the vast majority of them are actually harmless or supportive of the way our bodies work.

This article provides you an updated view of what is gut microbiota, it clarifies basic concepts in the field.

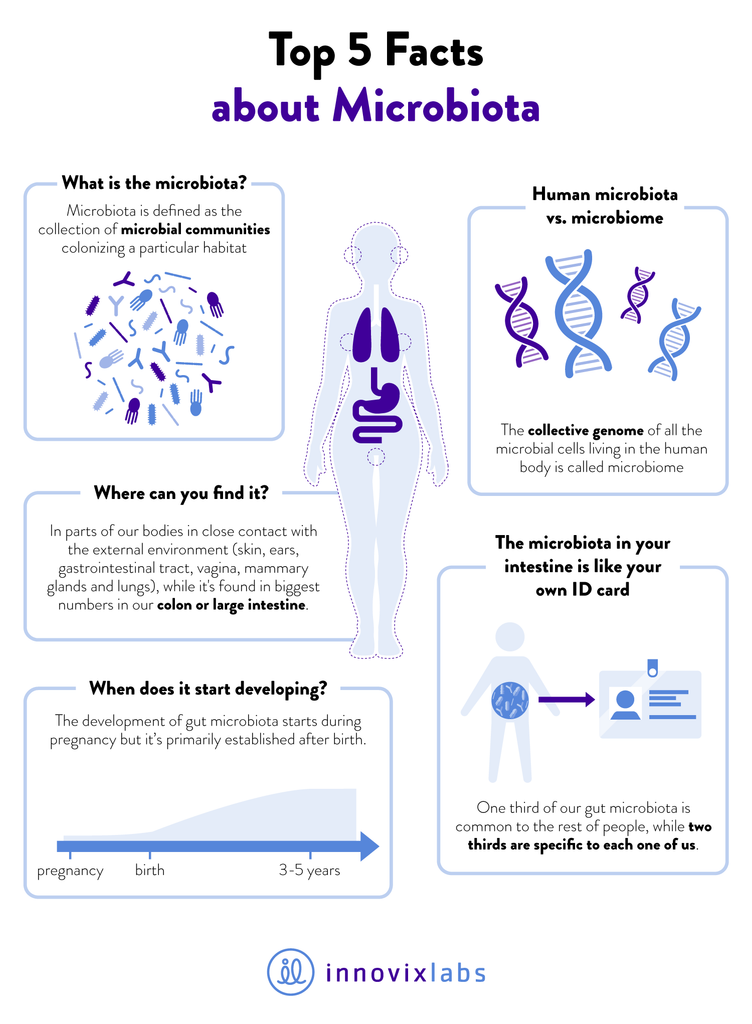

1. What is the microbiota?

The microbiota is defined as the collection of microbial communities colonizing a particular habitat. Although microbial foreign cells are much smaller and weigh much less than ours, as a whole we are home up to over 4 lbs of microbial cells.

Although initially the microbiota was called flora or microflora, these terms are no longer used by scientists because your inner microbial world consists of bugs instead of plants or flora.

Our human body is home to hundreds of trillions of microbes - not just bacteria, but also (gulp!) viruses, fungi and parasites (such as worms).

2. Human microbiota vs. microbiome: what’s the difference?

While microbiota refers to the composition of microorganisms living on and within us, the collective genome of all the microbial cells living in the human body is called microbiome.

Some scientists also use the term microbiome for the entire habitat shared with humans and their microbes, including not only communities of microorganisms (microbiota), but also their functions and the environment they inhabit.

Although the collection of microbes in our bodies are similar in number to our own human cells, they have more than 3 million genes, which is around 150 times more genes than we do. It's all a bit 'Men in Black,' we are mostly microscopic bugs in a human suit.

3. The colon or large intestine contains the highest amounts of bacteria

The microbiota is harbored in parts of your body that come into contact with the external environment. They include the skin, the ears, the gastrointestinal tract, the vagina, the mammary glands and the lungs.

However, the biggest population of microbes reside in the gut, with the greatest number in the large intestine.

The number of microbes increases by orders of magnitude as we travel from the stomach (low number of bugs) to the small intestines (higher) and then to large intestines and colon (much, much higher).

4. The microbiota in your intestine is like your own ID card

One third of our gut microbiota is common to the rest of people, while two thirds are specific to each one of us.

In other words, the gut microbiota composition is unique to each individual: it’s an individual identity card and it’s like our fingerprint that allows identifying us over time. Even identical twins have their own microbiome fingerprints.

It's just a matter of time before CSI: Microbiome airs on CBS. Criminals leave their skin microbiome behind at the scene of the crime.

5. When does it start developing?

Although intestinal bacterial colonization begins when a fetus is still in the maternal womb, an infant’s gut microbiota is mainly established after birth.

From the first day of life, the composition of the gut microbiota is directly dependent on how the baby is fed and the environment in which the delivery takes place.

Breastfed baby = more bugs and better bug diversity.

Natural birth (as opposed to C-sections) also means more bugs and better bug diversity.

Then, the microbial diversity increases and semi-permanently stabilizes by the end of the first 3-5 years of life.

Probiotics, antibiotics, and prebiotics may change the number and diversity temporarily, but in the absence of these three modifying factors, your gut microbiome fingerprint will simply revert to what it was before it.

This period is also known as “the window of opportunity for microbiota manipulation” and represents the most critical period for dietary interventions, with the goal of changing the gut microbiota to improve child growth and development.

The establishment of a really wide variety of bugs in a child's gut during this window of opportunity may influence the health of the child's entire life.

Breast feeding, presence of pet animals, outdoor play, minimal antibiotic use, wide variety of vegetables and fruits, all help to boost the variety of gut bugs in children before they are 4 or 5.

On the flip side, maternal antibiotic use, C-section delivery, formula feeding, indoor living, hyper-sanitation, and processed foods all reduce number of diversity of healthy gut microbiome.

Bottom-line:

- Your gut microbiome is made up of trillions of microbes, mainly bacteria, and their genes outnumber human genes 150 times.

- We can find the microbiota in different parts of our bodies in close contact with the external environment, while it's found in biggest numbers in our colon or large intestine.

- The microbiota in your intestine is as unique as an ID card. It has distinguishing features that can potentially be used to identify us over time.

- The development of gut microbiota starts during pregnancy but it’s primarily established after birth.

References:

Young VB. The role of the microbiome in human health and disease: an introduction for clinicians. BMJ. 2017; 356:j831.

Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 2016; 14(8):e1002533.

Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017; 474(11):1823-36.

Franzosa EA, Huang K, Meadow JF, et al. Identifying personal microbiomes using metagenomic codes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015; 112(22):E2930-8.

Rodríguez JM, Murphy K, Stanton C, et al. The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015; 26:26050.